UMass Chan Medical School researchers affiliated with the VA Central Western Massachusetts Health Care System are leading a $1.9 million multi-site Veterans Affairs merit review award study to close the gap in rehabilitation for patients with a disabling condition known as spatial neglect following right brain stroke. The study uses prism adaptation therapy to help patients regain visual-motor skills, and aims to identify through brain imaging which patients might respond best to prism adaptation therapy.

Spatial neglect is an imbalance in a person’s ability to know where they are in three-dimensional space, causing functional disability, explained principal investigator A.M. Barrett, MD, chair and professor of neurology. Even simple movements, like putting on and taking off glasses, require us to aim based on the three-dimensional shape of the object, our body and the space around us.

In most people, the right brain directs spatial function, while the left brain is dominant for language. So right brain spatial neglect can prevent people from dressing, eating, being mobile or otherwise functioning independently.

Yet, according to Dr. Barrett, fewer than an estimated 5 percent of people with right brain spatial neglect are considered for prism adaptation therapy, which has been shown in studies to be helpful in improving everyday function, and fewer than 1 percent receive treatment.

Barrett said, “If you can prevent one fall, or help someone be able to live without supervision, you can really make a tremendous impact.”

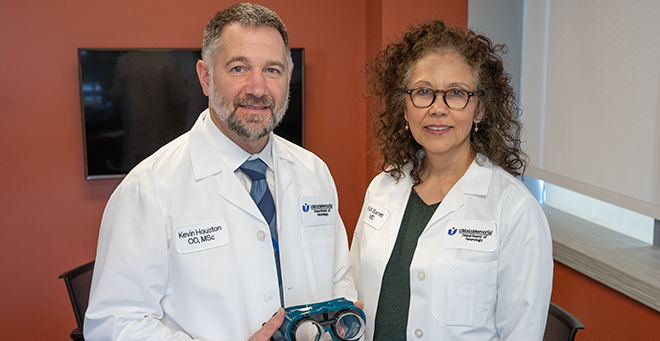

Barrett is leading the four-year VA study with Kevin E. Houston, OD, MSc, associate professor of neurology and co-investigator on the study. Cleveland VA Medical Center and Atlanta VA Health Care System are the other sites where the study is being conducted. Researchers hope to enroll 244 participants and include 120 with spatial neglect, who complete eight to 10 sessions of prism adaptation therapy in two weeks, while another 60 participants with right brain stroke but without spatial neglect complete baseline studies. Barrett and collaborators will use their brain imaging for comparison.

Therapists who administer prism adaptation therapy can be trained in less than a day. The therapy is a less time- and resource-intensive treatment than traditional stroke rehabilitation, which can last months and include inpatient and outpatient care.

In a prism adaptation therapy session, the patient dons goggles with wedge-shaped prisms that shift vision in the direction of the narrow end of the wedge, which for patients with left-sided spatial neglect is to the patient’s right. Through a series of exercises in which the patient repeatedly reaches to touch an object visualized through the goggles, which appears displaced to the right, the patient’s “spatial motor system is learning to amp up the leftward movements,” Barrett said.

“The treatment happens when you take the goggles off,” said Dr. Houston. “Over time the goal is for improvement to become permanent. It helps their brain recover the spatial movement.”

In formal studies, the effect of recovered spatial movement has been observed for several months, carrying over to improve patients’ function in everyday activities.

As part of the study, investigators aim to define and validate biomarkers through MRI brain imaging that might identify which people respond best to prism adaptation therapy. This information could be applied widely to identify veterans with right brain stroke who would be good candidates for the therapy, according to Barrett.