Many of us working in the “Gun Sense” field – that is, finding a middle ground position to advance firearm safety and reduce preventable injury in our patients – had an “a-ha” moment that led us to toil in these fields.

Mine was on Nov. 2, 1981, when my friend and co-resident Dr. John C. Wood II was shot right in front of our hospital emergency room at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in Washington Heights, New York City.

I have taken care of many gunshot wound victims since then, but none so difficult emotionally as this one. I participated in cracking my friend’s chest to start open cardiac massage and saw his heart devoid of blood from a through-and-through gunshot wound into his heart with a Saturday night special.

The survivability of a cardiac gunshot wound like this is close to zero, even though he was minutes away from the ER. He was in the OR and placed on cardiac bypass within 10 minutes of arrival. But his pupils were fixed and dilated and he had exsanguinated, or bled out, into his chest cavity. He did not survive despite our best efforts. It was an event that rocked Columbia and all who knew John, a fully boarded pediatrics-turned-surgical resident, a world-class Juilliard-trained French horn player and former Columbia rugby team captain.

The urgency of the firearm violence issue facing our country was heightened this past week when nine people were killed in three separate mass shootings over an 18-hour period in the U.S. In the past month, there have been attacks at places of worship, yoga studios and hospitals. Add these to the shootings in schools and in movie theaters and the tremendous sense of unease our citizenry is experiencing is completely understandable.

As physicians and surgeons on the front lines, many of my colleagues and I feel that it is no longer acceptable to treat this problem like our trauma team is a MASH unit. We have an obligation and an opportunity to reach out and speak out, and my hope is the country is listening. Because this is indeed our lane.

Watching the violence grow

My training took me to other cities, and everywhere the tragedy of firearm injury seemed to follow. I knew after that night in November ‘81 I could no longer practice in New York City, but I could not escape the parade of firearm tragedies. Children shot accidentally. Teens shot in gang wars. Teens and elders shooting themselves in impulsive moments of despair, yielding nearly 100 percent completion of their suicide task.

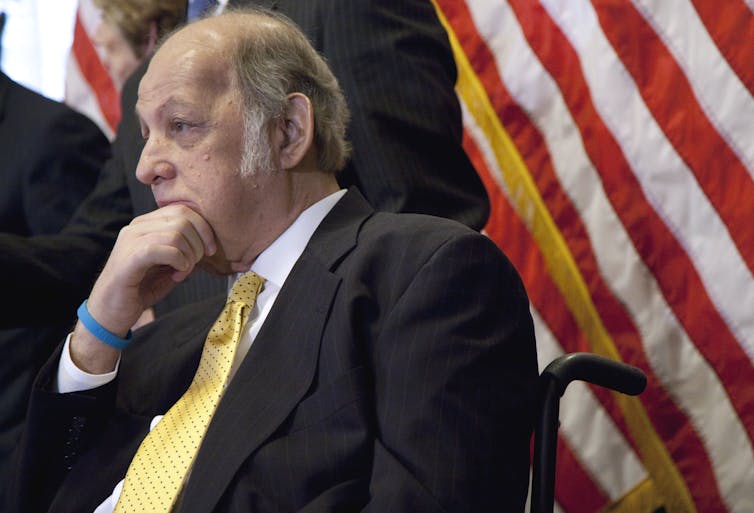

Gun violence increasingly became my focus when I heard Sarah Brady explain the concept of limiting access to lethal means. Sarah is the wife of Jim Brady, Ronald Reagan’s press secretary shot in the 1981 presidential assassination attempt. Brady spent the rest of his life partially paralyzed. He died in 2014, and the medical examiner ruled his death a homicide.

The Brady approach to gun control is limiting access. It is based on the premise that we might not be able to deal with the root causes of the violence – racism, poverty, mental illness – but that we could perhaps deal with the vector of violence that elevates all these factors into lethality – access to firearms. This is the philosophy behind the Brady Campaign, which aims to limit gun violence in the U.S. I began to wonder what I as an individual trauma surgeon could do to make a difference.

Looking for answers

In the 1990s, I was working in Pittsburgh as a pediatric trauma surgeon. A gang turf war over control of the crack cocaine trade broke out between the Bloods and the Crips. Both sides were heavily armed. As the body count rose on the north side of Pittsburgh where I was working, legislators tried to help by establishing a mandatory sentence for anyone in possession of a firearm when arrested for drug trafficking.

This caused the dealers to push the age of the drug runners to preteens and young teens, and they were equally armed. Our pediatric gunshot-wound patient victim numbers soared. When an 11-year-old was shot with an AK-47 in front of the mayor’s house, suddenly the city responded. Pittsburgh held community meetings. As director of a Robert Wood Johnson Injury Prevention Program, I was selected to represent the Allegheny General Hospital. The community disparaged our hospital as being insensitive and uncaring. Many believed we were “profiting” from the carnage and just sending the patients back out into the street to face more mayhem even if they had survived.

Our hospital encouraged my practice partner, Dr. Matt Masiello, and me to do something. We were both transplanted New Yorkers in the ‘Burgh, and we had heard about a new kind of gun buyback program in Washington Heights where a carpet store owner, Fernando Mateo, had emptied his inventory in exchange for locals bringing in their firearms. Previously, gun buybacks had only offered cash for the weapons. We decided to build a version of the program exchanging the guns for gift certificates to local merchants rather than actual merchandise. We collected 1,400 weapons that first year in 1994 and about 10,000 since then.

The buyback program has become much more than just a way to give the patrons the ability to rid their homes of unwanted or unsecured weapons. We built a public information blitz about the responsibility that goes along with the right to own a firearm, and we built awareness of the increased risk of suicide, homicide, femicide, accidental shooting, or breaking and entering for the purpose of stealing a firearm.

We have now reproduced the program in a number of cities across the U.S. In my hometown of Worcester, Massachusetts, working out of the UMass Memorial Medical Center, our multi-pronged approach to gun safety education coupled with the gun buyback has given us the distinction of having the lowest-penetrating trauma rate in New England.

In calendar year 2017, we had zero firearm fatalities, down from five the year before.

This was an astounding number, in view of national stats showing a rise from 33,000 deaths in 2010 to 38,000 in 2018. We faculty at the University of Massachusetts have built a curriculum for students at our medical school to empower doctors to ask the right questions in the proper way.

I am truly excited about the response my fellow physicians have demonstrated in their reaction to the National Rifle Association’s “stay in your lane” comments.

The NRA has already tried and failed to gag doctors in Florida from talking with their patients about gun safety.

In 2011, it backed a bill ultimately passed by the Florida legislature that would have forbidden doctors from asking patients about gun ownership or gun storage unless the doctor had a specific reason to do so. Doctors in violation could have been punished by loss of license and up to a US$10,000 fine.

“Physicians interrogating and lecturing parents and children about guns is not about gun safety,” read a letter from the NRA in support of the bill. “It is a political agenda to ban guns. Parents do not take their children to physicians for a political lecture against the ownership of firearms, they go there for medical care.”

Though it took six years to do so, the parts of the law that gagged doctors were overturned by the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in February 2017.

And now, even more than in previous years, doctors are saying they have seen enough – actually, way too much.

Now the awakening of the MDs gives me a sense of encouragement and hope that we as a profession can lead our country away from the intransigent position in which nothing gets done. Gun buyback is a middle-ground Gun Sense position that can rally a community around the cause that I have been fighting for since that dark day in November 1981. I hope other municipalities will join us, as these programs do work.![]()

Michael Hirsh, professor of surgery and pediatrics, University of Massachusetts Medical School

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.