Means, Motive, and Opportunity: Investigating the Role of Immune Cells in the Development of Type 1 Diabetes

Date Posted: Monday, July 19, 2021

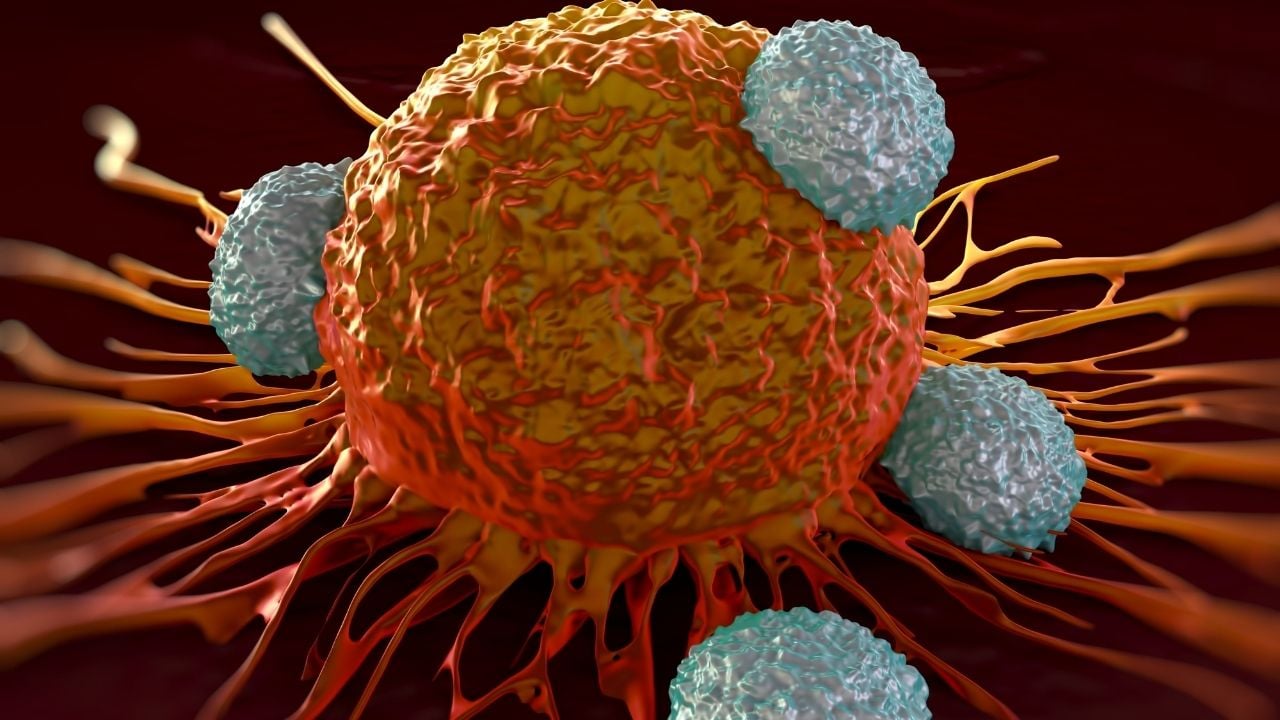

The islets of Langerhans are a cluster of cells within the pancreas. They’re responsible for the production and release of insulin and glucagon, the hormones which regulate blood glucose levels. Beta cells located within those islets are responsible for insulin production. In type 1 diabetes (T1D) a diverse assortment of immune cells infiltrates pancreatic islets. T cells are part of the immune system with the job of protecting the body from infection but are dysregulated in autoimmune diseases and attack ‘self’.

Scientists around the world continue to conduct extensive research to understand how and why immune cells in people with T1D attack their own beta cells. A newly published article in the scientific journal Frontiers in Immunology investigates the role of T cells at the “scene of the crime,” where the autoimmune attack occurs. A collaboration of nine scientists from the United States, Germany, France, and Sweden co-authored the article titled “Means, Motive, and Opportunity: Do Non-Islet-Reactive Infiltrating T Cells Contribute to Autoimmunity in Type 1 Diabetes?” It’s written in the narrative of a crime investigation in which T cells are the criminals that attack beta cells. They looked at means, motive, and opportunity of immune cells to attack insulin-producing cells, including T cells which may not be specific for the islets.

“Most of us have known each other for years,” said Sally C. Kent, PhD, associate professor of medicine and George F. and Sybil H. Fuller Foundation Term Chair in Diabetes at the UMass Chan Medical School Diabetes Center of Excellence. “I proposed to the group that we provide our perspectives about what T cells are seeing in islets of people with T1D.”

Insulitis is an inflammation of the islets. It’s caused by an invasion of immune cells that kickstarts the autoimmune response and results in destruction of beta cells. “Just because the T-cell is at the sight of the crime, it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re specific for reactivity to islets,” said Dr. Kent. “They may simply be bystanders pulled into the inflammation by other immune cells which are actually doing the attacking.”

Dr. Kent and her collaborators challenge scientists from around the globe to join them in investigating what role these cells play in T1D. Their article proposes several hypotheses and scenarios. They hope it inspires others to take a closer look at the immune cells that infiltrate the islets of people with T1D. “It’s becoming clearer that there is a broad repertoire of T cells infiltrating the islets and some kill the insulin producing beta cells,” said Dr. Kent. “We still don’t know what some types of T cells are seeing.”

Dr. Kent and her collaborators challenge scientists from around the globe to join them in investigating what role these cells play in T1D. Their article proposes several hypotheses and scenarios. They hope it inspires others to take a closer look at the immune cells that infiltrate the islets of people with T1D. “It’s becoming clearer that there is a broad repertoire of T cells infiltrating the islets and some kill the insulin producing beta cells,” said Dr. Kent. “We still don’t know what some types of T cells are seeing.”

One of the many challenges of studying these cells is that researchers are chasing a moving target. The behavior and observable characteristics of T cells change depending on the situation. In an inflammatory environment they can behave differently than if they were in a neutral environment.

“In my opinion, the biggest challenge is to understand what the immune cell infiltrate is doing in islets of people with T1D,” said Dr. Kent. “We still don’t understand what role each cell is playing, and how they interact with each other.”

Once they understand the interaction between cellular components and target tissue in islets during the autoimmune attack, it might provide insight into the cause(s) of T1D.

Related Stories:

Sally Kent Named Fuller Foundation Term Chair in Diabetes

Sally Kent receives Pioneer Award from the Network for Pancreatic Organ Donors with Diabetes (nPod)