It’s been almost two weeks since my last post on World Vitiligo Day because I just finished submitting a grant application to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to try to get funding to study vitiligo. After a pretty intense week of putting together our grant application, I’m sitting in my living room with my wife and watching the Red Sox play the White Sox as I write (the Red Sox are losing, in case you’re wondering). I thought this would be a good time to explain how this all works – getting financial support to conduct research on vitiligo.

It’s been almost two weeks since my last post on World Vitiligo Day because I just finished submitting a grant application to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to try to get funding to study vitiligo. After a pretty intense week of putting together our grant application, I’m sitting in my living room with my wife and watching the Red Sox play the White Sox as I write (the Red Sox are losing, in case you’re wondering). I thought this would be a good time to explain how this all works – getting financial support to conduct research on vitiligo.

The NIH is a government agency dedicated to supporting research that eventually improves the health of people in the United States and elsewhere. The NIH is directly supported by your taxes, and the budget they have to operate with depends on how much Congress decides to allocate there. This can change from year to year, but for over a decade the budget has remained flat, which when adjusted for inflation has resulted in decreased total funds for research and therefore fewer grants getting funded every year. One thing YOU can do is to support federal funding for research, and to tell your government representatives to do the same!

We also look at other funding agencies for research support, and our current supporters can be found here. The first step to convincing anyone to financially support research in a disease is to acquire preliminary data that suggests you’re “on to something”. We recently found an important signaling pathway that is responsible for causing vitiligo, so we think we’re “on to something”. We are now hoping to extend our studies to develop new tools to better diagnose vitiligo and predict a patient’s responses to treatment, to understand how it all works and, finally, to develop a new treatment for the disease.

To do this, I submitted a 65-page grant that summarizes what we’ve done, where we’re going, and how we plan to do it. Seems pretty straightforward, but there is only enough money to support the best 10-15% of all the submissions, so the application must be pretty outstanding. Grant reviewers read a large number of these applications and decide how important they are in comparison to each other. Where I submitted my grant, reviewers will see other grants on rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, psoriasis, and other skin, bone, and joint diseases. So we need to convince them that vitiligo is important (patients can help with this!), that our experiments will tell us some important information about the disease that will help patients, and that we’re the right team to do these experiments.

There are many ways to “skin a cat” so-to-speak or, in our case, to cure a mouse. We have to make sure that we’re using the right strategy that will produce the best results for patients in the fastest way possible. We’ve spent years thinking about these problems, putting our best guesses (hypotheses) to the test, and conducting preliminary experiments to show that we’re really “on to something”. Putting together an application like this takes months, and with the success rates so low, it gets very tiresome. But I have a really good team working with me, and it’s WHAT WE DO. Reading stories and comments about your struggles gives us motivation to keep going, and our successes make it a lot of fun along the way.

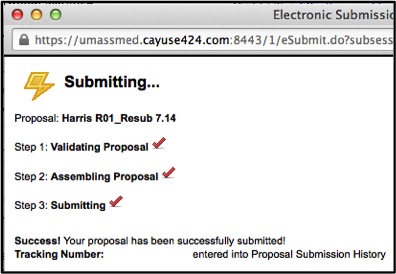

After hitting the submit button today, I walked into the lab to talk to “the team”. They showed me some pretty cool data, and we discussed some ongoing experiments. It reminded me how much I love my job and why I do this. I will be reminded again tomorrow afternoon when I see my patients in the Vitiligo Clinic at UMass Chan.