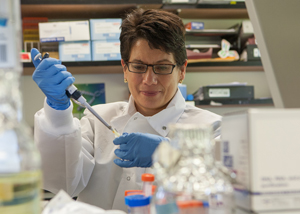

Katherine Luzuriaga, MD, works in her lab on continuing research to seek cures for HIV.

On the list of Time’s 100 most influential people of 2013 are the usual assortment of celebrity musicians, actors, athletes, politicians and businesspeople—and Katherine Luzuriaga, MD. Dr. Luzuriaga, professor of molecular medicine, pediatrics and medicine, and vice provost for clinical and translational research, was recognized along with two colleagues, Hannah Gay, MD, and Deborah Persaud, MD, for their functional cure of an HIV-positive infant. More than just a chance to hobnob at the gala reception, the doctors’ collective inclusion on the Time list sends an important message about science and medicine in the United States today.

“Our inclusion on the Time 100 list places science in the public eye and in a very favorable light,” said Luzuriaga. “Any time the popular press recognizes a scientist and the importance of the scientific process in changing our lives, it’s a good thing.” That kind of recognition could lead to a better understanding by the general public of what it means for their tax dollars to support researchers through NIH funding, as well as to encourage donations to foundations or academic institutions to support further research. And that, in turn, “can create wins for patients,” said Luzuriaga.

The case involved an infant born to a woman who had not received prenatal care and therefore had not been diagnosed as HIV positive before delivery. When the child was born, Dr. Gay, a pediatrician at the University of Mississippi, started therapeutic antiretroviral treatment within 30 hours of birth, even before the baby tested positive for HIV. Unlike the standard prophylactic treatment, which is administered for six weeks and followed with therapeutic doses only after an infection is diagnosed, this more aggressive approach continued until the child was 18 months old, when the mother stopped coming for follow-up visits. After five months in which no additional treatment was administered, the child’s blood was retested with standard measures. No trace of HIV was detectable; there was also no sign of HIV-specific antibodies.

Gay consulted with Luzuriaga, who immediately contacted a long-time colleague, Dr. Persaud, associate professor of pediatrics and infectious diseases at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center. Luzuriaga and Persaud used highly sensitive molecular virology and immunology techniques to evaluate the baby’s blood for persistence of HIV. The baby has remained healthy and has not experienced an HIV rebound in follow-up. The team’s paper reporting the case was published in the Oct. 23 online edition of the New England Journal of Medicine.

The so-called “Mississippi baby” is just one case, but the takeaway—that ongoing treatment initiated early in an infant’s life has the potential to cure HIV infection—is significant. There is a big if, however, and that’s whether it’s possible to routinely diagnose newborns. Standard diagnostic methods use antibodies to search for infection but, because of the third-trimester maternal transfer of antibodies, that’s not a perfect approach. Properly diagnosing an infant, then, requires nucleic-acid-based detection methods to find any HIV nucleic acids in plasma, which calls for a lab with trained technicians—at a significant cost. It’s not practical in many parts of the world where HIV remains unchecked so, as of now, the best chance of eliminating maternal-child transmission remains testing during pregnancy. With the mother on antiretrovirals, transmission rates drop to near zero.

The functional cure itself was two decades in the making. In 1987, Luzuriaga arrived at UMass Medical School as a fellow in viral immunology in the lab of John Sullivan, MD, professor of pediatric immunology & infectious diseases. Together, they established a maternal-child AIDS clinic in response to the growing numbers of HIV-positive mothers and children. Through the new practice, they could directly address the speed with which signs of infection progressed in children—by age 2, more than 50 percent of HIV-positive children will be severely symptomatic. They were also part of NIH’s clinical trials network and, through that, were able to conduct an initial set of studies on infants and treatments that would test their hypothesis that early treatment could alter both the clinical course and, potentially, set points of latency.

“Everything we did was going bench to bedside,” said Dr. Sullivan, “and back to the bench.” In 1997, with Luzuriaga as principal investigator, they published their findings in the New England Journal of Medicine that intervention within the first three months of life with a combination of zidovudine (AZT), didanosine and nevirapine was effective at suppressing HIV infection.

Many of the clinic’s patients were from families across the region, so Luzuriaga and Sullivan established locations in Lowell and Lawrence. Many families were stressed socioeconomically so they built a team that included social workers and others to provide global assistance to families, and covered travel, phone bills and food costs, as needed. With proper adherence and careful use of AZT, the number of new patients gradually dropped. Today, the average age of clinic patients is 16, and the focus is on longer-term health issues including management of lipids and a healthy diet. After a lifetime of antiretroviral therapy, such patients may be at greater risk of diseases related to aging—in particular, coronary disease—and Luzuriaga and her team are engaged in long-term follow-up studies of the consequences of early exposure to antiretrovirals.

“We’ve made significant strides,” she said, “but are there newer issues that they may face as they go along?”

Luzuriaga remains concerned about women and newborns who aren’t treated early on. The standard recommendation is that every pregnant woman be tested for HIV; anyone who presents at labor and delivery with no documentation of having done so receives a rapid test. In the United States, Europe, Australia and Thailand, some 30 percent of infants born to HIV-positive mothers who were not treated with antiretrovirals while pregnant will be infected—the Mississippi baby is one such example. With antiretroviral therapy, less than 1 percent of infants are born infected, which translates to about 100 cases annually in the United States. The numbers are higher in sub-Saharan Africa, where the penetration of interventions has not been as extensive; in low-resource settings, a better infrastructure is needed to get medications to patients and simultaneously ensure their adherence.

“There are places in the world where this experiment can be continued to show that the result is, in fact, real,” said Sullivan of the Mississippi baby case, “and then people can begin to think about applications that go beyond.”

Luzuriaga and Persaud have recently collaborated with the NIH-sponsored International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials network to develop a protocol to test whether very early potent antiretroviral therapy can clear HIV infection in infants. Data from several small adult studies also suggest that early treatment may allow some adults to eventually go off therapy and control their infection.

Collaboration will be key to learning how the virus-host dynamic plays out, and in moving from the lab to the clinic. To further those efforts, Luzuriaga was involved with the founding of the Center for Clinical and Translational Science, which spans the five UMass campuses and which she now directs. UMCCTS allows for the creation of multidisciplinary teams to address myriad medical issues; build devices that can be used in diagnosis or patient management; or take advantage of skills and equipment, such as a request for the creation of a specific protein or the use of a mass spectrometer. It is, said Luzuriaga, “an institutional attempt at building capacity for generating cross-disciplinary collaborations that will facilitate translation of basic science discoveries.” The collaboration also incorporates UMass Medical School’s MassBiologics, the only non-profit, FDA-licensed manufacturer of vaccines and biologic products in the United States, providing opportunities for cross-campus biologics manufacturing.

One impetus behind the establishment of the UMCCTS was to pair UMMS with the University’s Lowell-based engineering program, and an early outcome was the Massachusetts Medical Device Development Group, better known by its acronym M2D2. The not-so-veiled reference to Star Wars suits Luzuriaga, who said that long before she went to MIT as an undergraduate, she was very much at home in the world of science and math students.

Born in Venezuela, Luzuriaga was raised in the Philippines, first coming to the United States to attend college. She’d planned to be a primary care pediatrician, but her passions for microbiology and immunology found a focus during her second year of medical school, when the first descriptions of patients with AIDS appeared in the literature. With a month to design and complete an elective—she’d spent her first two years at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine before transferring to Tufts University School of Medicine—she chose viruses and the immune system and was, she said, “hooked.” She trained in pediatrics and infectious disease, and arrived at UMMS as a fellow prepared to begin research in viral immunology, specifically the

Epstein-Barr virus. But the sudden rise in numbers of HIV-infected women and infants led to a refocusing of Luzuriaga’s energies.

Nearly three decades later, Luzuriaga is pleased that researchers know as much as they do about HIV, observing that it is better understood than many other viral infections. She attributes that to a strong patient advocacy effort, coupled with NIH-funded advances in technology, basic understanding of HIV infection, and HIV clinical trials. Continuous NIH funding, along with backing from organizations that include the American Foundation for AIDS Research and the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation has been key. Luzuriaga was named an Elizabeth Glaser Scholar in 1994 and an Elizabeth Glaser Scientist in 1997. She continues to collaborate with other Elizabeth Glaser scientists, including Persaud and UMMS colleague Paul R. Clapham, PhD, associate professor of molecular medicine and microbiology & physiological systems, observing that the human relationships the funding fosters have resulted in better science through collaborations. The success with Gay and Persaud was possible because they were able to move quickly, thanks to the framework provided by NIH and the other funders.

Luzuriaga’s own children are 18 and 22 years old. She was pregnant with her first son alongside her early clinic patients, and notes somberly that many of those women and their children are no longer living.

“But by the time I had my younger son,” she said, brightening, “we had ARVs we could use, and almost all of those kids are alive. That’s been gratifying.”