UMass Chan Podcast on Simulation in Medical Education Addresses Rising Interests in New Learning Methods in Curriculum Revolution Project

WORCESTER, Massachusetts, Apr 9, 2021 – Former Simulation Interest Group (SimIG) student leader Trenton Taros and Director of Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) Simulation Dr Nasim Gorji, DO joined hands with Simulation Educators Anne Weaver, RN, MS and Jorge Yarzebski, BA, NRP, FP-C to address rising interests in the use of simulation to enhance their approach to medical education.

“Many build teams are considering incorporating simulation in their block planning because it is a highly effective and engaging learning strategy,” wrote Dr. Trish Seymour, Clinical Pillar Lead of the Curriculum ReVolution Leadership Team (CRLT), in a weekly address to faculty, administrators and students who are involved in the formation of UMass Chan Medical School’s Curriculum ReVolution project which is currently underway.

During the podcast titled “Simulation in Medical Education”, which is still available on open access, the panel highlighted 5 key points:

- Simulation provides hands on learning that’s really favored by the learners

- Simulation is a great patient safety strategy in medical education

- Simulation can address low frequency learning events that are high stakes

- Simulation is high value for both observer and participants

- UMass Chan Medical School iCELS Department is willing and excited to work with faculty no matter how little experience faculty have in designing simulation activities

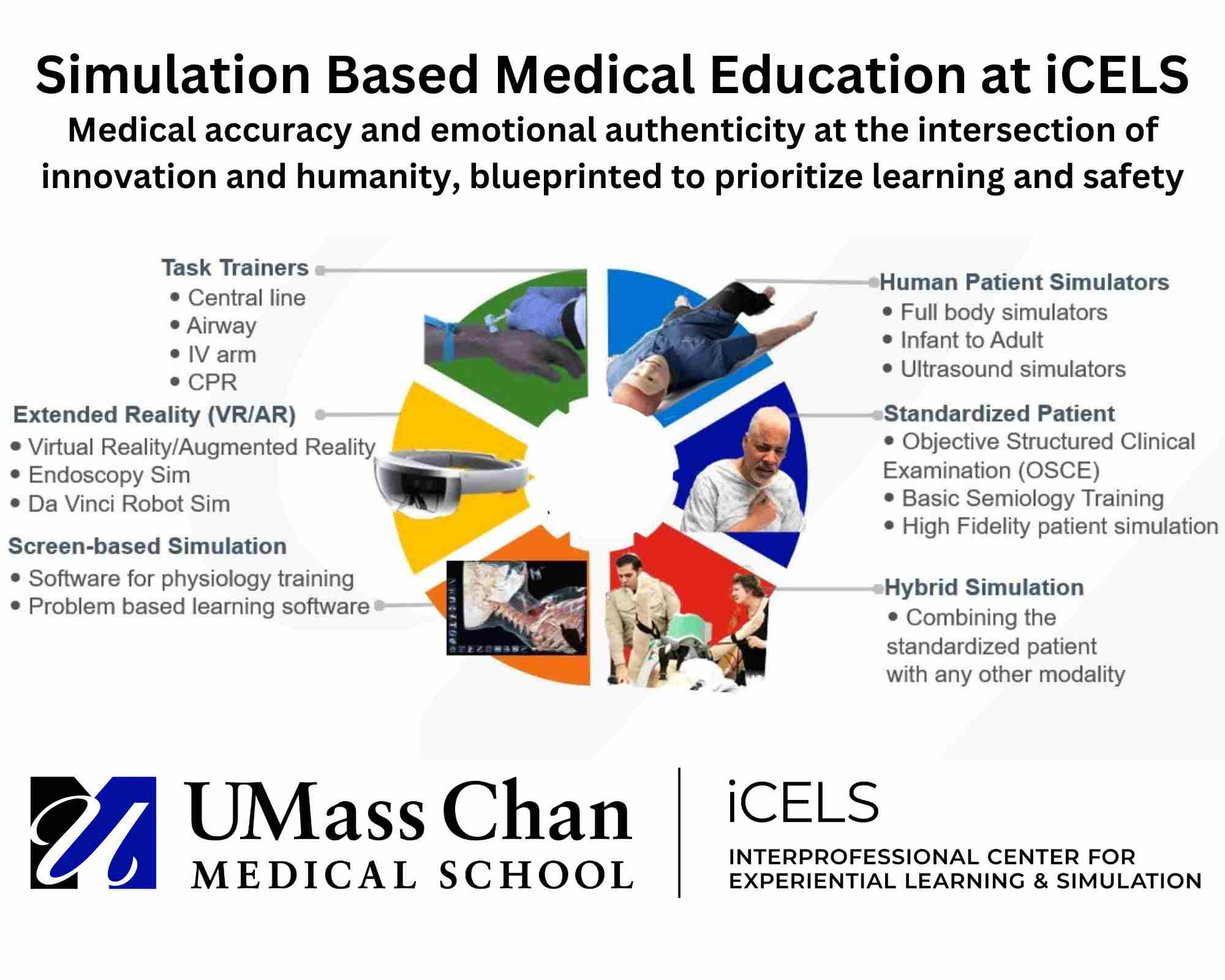

“There are many types of simulation in use at UMass Chan Medical School. We have a very talented pool of standardized patients (SPs) – actors who are trained not only to portray a patient or family member, but also highly trained to give feedback so they are able to really help our curriculum,” Weaver introduced. “Furthermore, in hybrid simulations, we combine the actor or SP with a human patient simulator. Human patient simulators can be very high-tech, such as in the case of a manikin which can mimic a human person with heartbeat, lung sounds, bowel sounds, pulses. They can cry, sweat, vomit, make noises. They can also be low-tech, less technical task trainers – possibly just an airway head, an intravenous arm, a pelvic trainer, a trainer for lumbar puncture – which provide practice ahead of doing so on a live person. We also have screen-based learning for simulation, as well as Extended Reality which many people know as Virtual Reality, to help achieve the learning objectives.”

“There are many types of simulation in use at UMass Chan Medical School. We have a very talented pool of standardized patients (SPs) – actors who are trained not only to portray a patient or family member, but also highly trained to give feedback so they are able to really help our curriculum,” Weaver introduced. “Furthermore, in hybrid simulations, we combine the actor or SP with a human patient simulator. Human patient simulators can be very high-tech, such as in the case of a manikin which can mimic a human person with heartbeat, lung sounds, bowel sounds, pulses. They can cry, sweat, vomit, make noises. They can also be low-tech, less technical task trainers – possibly just an airway head, an intravenous arm, a pelvic trainer, a trainer for lumbar puncture – which provide practice ahead of doing so on a live person. We also have screen-based learning for simulation, as well as Extended Reality which many people know as Virtual Reality, to help achieve the learning objectives.”

From the Learner’s Perspective

Taros from the T.H. Chan School of Medicine’s Class of 2022 kicked off the sharing. “In general, everyone loves simulations. This is especially true in our pre-clinical year. We were so much in our head, so cerebral, we’re learning so much - we understand that’s the nature of medical school, we need good bases to become a great clinical, but we also need skills that are taught by hand. Students yearn for that experience. During the first year in medical school, we look forward to the simulation sessions so much, they would be circled in our calendars for weeks ahead,” he recounts.

A few simulation activities have been integrated into the UMass Chan Medical School curriculum -anatomy, respiratory, cardiac, musculoskeletal (MSK), gastrointestinal (GI) and renal units. By the third year, simulation would cover a range of crucial skills including arterial blood gas (ABG) and lumbar puncture. “Nobody wants to do their first one on a patient, and no patient want to be our first lumbar puncture. That’s where simulation really shines,” Taros highlights.

Asked about his favorite simulation activity, Torres pointed out a scrub training session that was hosted and organized by the student organization SimIG. “We were able to practice how to actually scrub in, do the gowning, observe Operating Room (OR) etiquette – the fine points on what to do and what not to do. iCELS is equipped with a full surgical suite so this was high fidelity experience. On addition, we had a good mix of hybrid simulation with a manikin functioning as the patient,” he shares. “Then we wrote a paper that was presented at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) conference. It was well-received because it was entirely run by the students and for the students.”

Learner-initiated SimIG events are geared towards teaching pre-clinical medical students procedural skills that can then be utilized in real world clinical settings, with an emphasis on providing better healthcare to underserved populations. During the pandemic, it adapted by holding offsite sessions. “We ran a virtual simulation for casting training by dropping off Ziploc bags full of plaster and wool undercast material to fellow students, and walking through the casting process on Zoom,” Taros says.

Gorgi, who first experienced simulation at UMass Chan Medical School as a resident and now leads NICU simulations, resounds. “Now more than ever there is a movement toward multi-disciplinary hands-on interactive learning over traditional didactic instruction. Simulation allows learners from different disciplines to come together to work on problem solving, skill acquisition and communication skills.“ She also lauded the availability of simulation during challenging times. “We have witnessed firsthand during this pandemic that it is possible to adapt cases to virtual platform and many circumstances, which taught us a lot about flexibility and possibility,” Gorji affirms.

An Effective Medical Education Strategy

“Simulation is such an effective learning tool because we’ve moved away from the apprenticeship model of education. We’ve been able to create learning spaces in the medical school that allow educators to deliver practical, measured, safe experiences for authentic tasks that are needed in medical school. These tasks can be supported through deliberate practice that can be replicated and debriefed,” Yarzebski observes from his 12 years as a simulation educator.

“In this respect, simulations deliver learner-centered opportunities that are founded in great educational theories, and (follows the principle of) universal design for learning – learning from lectures, from patients at the clinical sites, but also from this low-stakes safe environment that is safe for patients as well as for the learners. These environments can be supported, replicated, and repeated numerous times without any risk to the patient or the student,” Yarzebski says.

“With patient centered care, the limit is your imagination and your buy-in. With procedures and skill attainment we can do scenarios, difficulty conversations, disruptive behaviors, trauma, surgery, medicine – the whole span can be simulated at our center,” he says. During systems training such as the use of electronic health record (EHR), learners who did not have the skills to contribute to resuscitation yet had adapted to utilizing their skills in reading the charts, extracting valuable information about history, medication, allergies, and more – which many students were unfamiliar with before the simulation.

Simulation in Low Frequency, High Stakes Situations

As patients experience shorter hospital stays there are less opportunities for students to interact with patients. In this respect, Yarzebski emphasizes that simulation can also be used to re-create these occurrences, as well as those that are rare to encounter at clinical rotations.

“It is really valuable for low frequency and high acuity cases because we can replicate things that student might not experience clinically or some might have experienced it once when they were unattended. We can with deliberate practice e go over common important skills as basic as handwashing to scrubbing to suture, airway, IVs, central lines, all those common procedural skills – we can target sensitive and vulnerable populations as well – students might not have opportunity to care for those patients, but it allows for an inclusive model for education,” Yarzebski highlights.

Proven to Help Both Observers and Participants

“The role of observer in simulation has been studied. The learning is proven to be as effective and long lasting as the role of the person participating,” Weaver points out. This supports the practice of having some learners in the observing role and others in the active simulation role, which the team has taken in view of pandemic safety precaution.

“The biggest challenge to many learners is the mix of emotion - in terms of wanting to do well but nervous they’re being watched or would not do well. Simulation is a great opportunity to help students deal with those emotions in the pre-brief and debrief period,” Weaver affirms. The experienced simulation education is also known to many learners - including former student Gorgi who is also present at this podcast - as a prolific debriefer.

Of her most memorable simulation experience over the years, Weaver recalls a student who had said at the start of the simulation, “I hope I make a really big mistake because that way I know I’ll never make that mistake in real life.” To this point, Gorgi added her observation at NICU simulations, that the most outstanding sessions were indeed when learners identified their own learning gaps and prompted active discussions that transcended pre-planned teaching points.

Helping Faculty Get Started with Simulation

With many encouraging signs pointing to increased use of simulation in medical curriculum, where do faculty members start?

“We work with you to develop simulations. On iCELS website you can start that process by putting in for a request. Based on the objectives you share, we can decide what type of simulators we need to include, what size of group needs to be for optimal learning. We can contact the person who’s interested to write up the cases. We can also do in-situ simulation whereby we gather our equipment and bring it to the actual clinical setting that is meant to be represented and do that there,” Weaver explains.

“Reach out as soon as you know you want to start because it takes time to develop. The reason it takes time is that the development process involves doing dry runs and making sure it produces a sound learning opportunity for the learners. We want to be involved in that process right away,” she enthuses.

On the capacity to handle increased sim activities that come along with the curriculum renovation projects, Jorge affirms that iCELS has been operating on a model of growth by restructuring the team to support increased demand. “We’ve adapted to welcome the larger class sizes but also integrating more faculty – training up that faculty to reach the larger number of students. If that includes expanding hours and offering evening simulation opportunities, we are open to it and we would meet that demand,” Jorge says.

As group sizes are often dictated by number of instructors available, UMass Chan Medical School is offering faculty development sessions to those interested to serve as debriefers and facilitators at simulation sessions. This training provides a framework and toolset on how to debrief, and it includes an opportunity for the faculty members to participate in roleplay exercises as well.

Simulation as Part of the Ongoing Curriculum ReVolution

Led by Melissa Fischer, MD, MEd, the mission of the UMass Chan Medical School Curriculum ReVolution is to develop a contemporary and innovative curriculum that promotes curiosity and inquiry, empowers learners and enables future physician leaders to equitably and expertly care for diverse patient populations. The new UMass Chan curriculum is being designed to:

- Attract and support a diverse student body

- Develop expertise and application of biomedical, clinical and health system sciences

- Foster commitment to service and advocacy for patients and populations

- Apply modern educational practices and engaged pedagogy

- Promote collaboration with peers, interprofessional colleagues and faculty

- Address the impact of social determinants of health, racism and bias on healthcare access and delivery

- Leverage technology to improve learning and the care of patients and populations

- Stimulate self-directed and self-informed learning and professional identity formation

- Anticipate and adapt smoothly with the evolution of medicine and healthcare

- Nurture innovation, scholarship and discovery in our learning environment

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

Patricia Seymour, Anne Weaver, Jorge Yarzebski Jr., Trenton Taros, Nasim Gorji, Melissa Fischer. Simulation in Medical Education. Curriculum ReVolution by Office of Undergraduate Medical Education at UMass Chan Medical School. Podcast on April 9th, 2021. Accessible online at https://soundcloud.com/patricia-seymour-140768045/simulation-in-meded