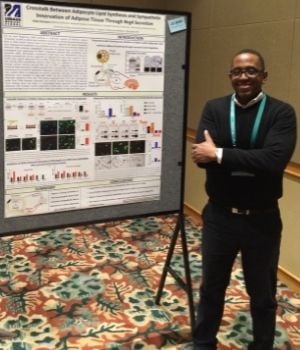

Type 2 Diabetes Researcher Spotlight: Adilson Guilherme, PhD

Date Posted: Tuesday, November 09, 2021

Dr. Guilherme is an Associate Professor in the laboratory of Michael Czech, PhD at UMass Chan Medical School. He joined the lab for his first postdoctoral position in 1995 after earning his PhD in Biochemistry from Federal University in his home city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The main focus of his current research is fat cell metabolism and biology, and investigating beige fat as a therapeutic potential for people struggling with obesity, diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

Growing Up in Rio de Janeiro

Adilson had a humble upbringing as the youngest of eight children. “My parents could not read or write,” he said. “My father worked construction. They were good people and taught me strong values at a young age.”

His mother encouraged him to focus on education. “She knew that would be my ticket to a better life and keep me out of trouble, especially growing up in Rio, where unfortunately crime was high.” As far back as he could remember, Adilson enjoyed science. He was first introduced to biology in elementary school. “It’s been my passion ever since,” he said. “The way the cells metabolize fascinated me. I wanted to learn more.”

The college admission process in Brazil is quite competitive. Tuition is free and enrollment is based on entrance exam results. Adilson was thrilled to be accepted to Federal University, one of the largest and best-known universities in Brazil. It also has one of the strictest admission policies in the world, accepting only 1 out of 10 applicants.

As an undergraduate he majored in cell biology and became interested in insulin signaling in diabetes and obesity. “I spent a lot of hours in the lab my first year,” he said with a big smile. “I found my niche. I knew I belonged there.” Adilson authored his first research publication while still an undergraduate student. It was a study of kidney function and how insulin regulates the transport of calcium in kidney cells. “I’m proud to have published that first paper in my early 20’s,” he said. That project spawned his interest in insulin signaling, and he earned his master’s degree followed by a PhD in Biochemistry.

Science Lesson Learned Early

Early in his research career Adilson learned an important lesson that he’s passed along to younger lab members over the years. While studying kidney transport, which would eventually become the topic of his thesis, he had trouble getting enzymes to work consistently within the biological system. He soon realized the problem wasn’t the science. “I was getting distracted,” he admitted. “There were fun people in that lab, and we talked and joked while we worked.” He started to work in the lab on weekends when nobody was around. "Suddenly the experiments were working beautifully. I’m glad I learned that early on,” he said. “If you’re conducting experiments while talking and the data is all over the place, that means you’re distracted. For me, research required my full attention and focus.”

Introduction to The Czech Laboratory at UMass Chan Medical School

During his studies as a PhD candidate, Adilson read several papers authored by Dr. Czech and was impressed with his lab scientific productivity and their beautiful papers describing new aspects of the fat cell’s metabolism. He also followed the progress of others in the field who were investigating insulin signaling pathways in the adipocyte and discovering several key elements. “Their work built the foundation of insulin signaling, not only in the adipocytes, but also in other metabolic tissues,” he said. “Their data provided new insight into obesity and diabetes, and it excited me.”

Much of that research was taking place in Massachusetts, so Adilson decided to look into those labs. “I took a chance and contacted Mike to see if he would accept me as a postdoc in the Czech Lab,” he said. “Not only did he offer me a job, but he provided a welcoming environment for someone coming from another country with a different cultural background and who didn’t speak any English!”

Adilson feels lucky to have a career doing something he’s passionate about and enjoys so much. “I’m fortunate to have been able to work in the same lab for many years,” he said. “He [Dr. Czech] creates an outstanding environment to conduct research. He has always encouraged and supported me to address the scientific questions I’m interested in and has allowed me to develop scientifically.”

Career Highlights

One of Adilson’s career highlights thus far was his involvement in the development of small interfering RNA (siRNA) screens as a therapeutic tool to address cellular and molecular mechanisms of inflammation, obesity and diabetes. RNA interference was a new technology discovered in part by Craig Mello at UMass Chan Medical School, for which he was awarded a Nobel Prize in 2006. Adilson was on the team of scientists who figured out how to knockout certain genes in adipocytes to discover which genes control glucose transport and insulin signaling in fat cells. That work in the Czech Lab has since been extended to the use of self-delivery RNA (sdRNA) and the development of vehicles for delivery of CRISPR-based gene editing.

From the late 1990’s through 2010 they performed proteomics analysis of glucose transporter-containing membranes from adipocytes to study how and why insulin stimulation allows blood sugar to enter those cells. In 2002 the Czech Lab published a paper in Nature describing their discovery of a molecular motor they found to be essential for insulin stimulation of glucose transport into fat cells. Adilson identified his participation in that research as another career highlight. “We know other labs, both in US and other countries, have independently confirmed our findings that Myo1c (the molecular motor) is essential for glucose transport in adipocytes,” he said.

Future Research Goals

As he continues to work on current projects, new questions arise that he would like to investigate. Among them include the following.

Understanding the role of fat cells in systemic metabolism has changed dramatically since mid-1990s. “Prior to 1994 adipocytes (fat cells) were thought to simply store accumulating fat,” he said. “That’s no longer true. Over the past 25 years we’ve learned that they are endocrine cells that secrete hormones, communicate with other organs and tissues, and can dramatically change our entire body’s physiology and metabolism.” He cited leptin as an example of a hormone that gets secreted by fat cells and sends signals to the brain to help people maintain body weight. Leptin inhibits hunger responses when we don’t require energy. Since it’s secreted from fat cells, the amount of leptin in the body is the result of how much body fat an individual has. When we gain body fat, leptin levels increase and when our body fat percentage drops, leptin levels decrease.

Adilson is excited for future research to determine what additional hormones adipocytes are secreting, then studying those to determine if mutating or deleting them may offer therapeutic potential for people struggling with obesity, diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

Various classifications of fat have been discovered during Adilson’s scientific career. The field has determined that not all fat is created equal. White fat cells can accumulate in our bodies and cause health problems. Others such as brown fat and beige fat have been found to burn calories by turning fuel into body heat. “Until the early 2000’s it was believed throughout the field that only small animals and newborn humans contained beige cells to produce heat and control body temperature,” he said. “It’s now known that beige fat cells exist in adult humans, and their thermogenic roles may provide benefits.”

Another project the Czech Lab is working on is investigating ways to increase the number of beige cells and/or converting “bad fat” into “good fat” as a potential therapy for obesity and diabetes.

The overarching questions he’s interested in includes how adipocytes control systemic metabolism, and does it have anything to do with the hormones and peptides they’re secreting? Also, how adipocytes fail when they store too much fat? For example, how and why does obesity lead to diabetes and cardiovascular disease?

About Dr. Adilson Guilherme

While science is his biggest passion in life, Adilson enjoys traveling the world and learning about different cultures. He’s trilingual, speaking his native Portuguese as well as Spanish and English. When he left Brazil for the first time and arrived in Massachusetts in 1995, he spoke absolutely no English. He became a United States citizen in 2017 and now has dual citizenship. 2017 was also the year Dr. Guilherme was promoted to Associate Professor in Molecular Medicine.

He enjoys watching soccer. “As a Brazilian it’s mandatory to like soccer,” he joked. He reads quite a bit in his spare time. While he loves world travelling, he also appreciates all that New England has to offer just a car ride away. He takes advantage of Worcester’s many restaurants, cultural scene, and activities.

Related Articles

Type 2 Diabetes Research in the Czech Lab Investigating Beige Fat to Potentially Increase Metabolism

Molecular pathways linking adipose innervation to insulin action in obesity and diabetes mellitus

Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes